The First Signs of Trouble

Contents

Audio Version of the Scene

Modern Text Version

Elsinore. A platform before the castle. The First Signs of Trouble

| Original Text | Modern English |

|---|---|

| FRANCISCO at his post. Enter to him BERNARDO | Francisco is on guard duty. Bernardo enters to join him. |

| BERNARDO: Who’s there? | Who’s there? |

| FRANCISCO: Nay, answer me. Stand, and unfold yourself. | No, you answer me. Stop and identify yourself. |

| BERNARDO: Long live the king! | Long live the King! |

| FRANCISCO: Bernardo? | Is that you, Bernardo? |

| BERNARDO: He. | Yes, it’s me. |

| FRANCISCO: You come most carefully upon your hour. | You’re right on time for your shift. |

| BERNARDO: ’Tis now struck twelve. Get thee to bed, Francisco. | It’s just gone midnight. Go to bed, Francisco. |

| FRANCISCO: For this relief much thanks: ’tis bitter cold, And I am sick at heart. | Thanks for the relief. It’s bitterly cold, and I feel depressed. |

| BERNARDO: Have you had quiet guard? | Has your watch been peaceful? |

| FRANCISCO: Not a mouse stirring. | Not even a mouse has stirred. |

| BERNARDO: Well, good night. If you do meet Horatio and Marcellus, The rivals of my watch, bid them make haste. | Well, goodnight. If you run into Horatio and Marcellus, who are coming to share the watch with me, tell them to hurry. |

| FRANCISCO: I think I hear them. Stand, ho! Who is there? | I think I hear them now. Halt! Who goes there? |

| Enter HORATIO and MARCELLUS | Horatio and Marcellus enter. |

| HORATIO: Friends to this ground. | Friends of this land. |

| MARCELLUS: And liegemen to the Dane. | And loyal subjects of the Danish king. |

| FRANCISCO: Give you good night. | Goodnight to you. |

| MARCELLUS: O, farewell, honest soldier: Who hath relieved you? | Farewell, honest guard. Who’s taking over your watch? |

| FRANCISCO: Bernardo has my place. Give you good night. | Bernardo is relieving me. Goodnight. |

| Exit FRANCISCO | Francisco leaves. |

| MARCELLUS: Holla! Bernardo! | Hey! Bernardo! |

| BERNARDO: Say, What, is Horatio there? | Tell me, is Horatio with you? |

| HORATIO: A piece of him. | Part of me is here. |

| BERNARDO: Welcome, Horatio: welcome, good Marcellus. | Welcome, Horatio. Welcome, Marcellus. |

| MARCELLUS: What, has this thing appear’d again to-night? | So—has the thing appeared again tonight? |

| BERNARDO: I have seen nothing. | I haven’t seen anything. |

| MARCELLUS: Horatio says ’tis but our fantasy, And will not let belief take hold of him Touching this dreaded sight, twice seen of us: Therefore I have entreated him along With us to watch the minutes of this night; That if again this apparition come, He may approve our eyes and speak to it. | Horatio thinks it’s just our imagination and refuses to believe in the terrifying sight we’ve twice seen. That’s why I persuaded him to join us tonight, so that if the ghost appears again, he can confirm what we’ve seen and maybe speak to it. |

| HORATIO: Tush, tush, ’twill not appear. | Nonsense, nonsense — it won’t appear. |

| BERNARDO: Sit down awhile; And let us once again assail your ears, That are so fortified against our story, What we have two nights seen. | Sit down for a while, and let us once more attack your stubborn ears with the story of what we’ve seen these past two nights. |

| HORATIO: Well, sit we down, And let us hear Bernardo speak of this. | Very well, let’s sit down and hear Bernardo tell it. |

| BERNARDO: Last night of all, When yond same star that’s westward from the pole Had made his course to illume that part of heaven Where now it burns, Marcellus and myself, The bell then beating one,— | Last night, when that very star you see there west of the North Star had travelled to shine in that part of the sky where it is now, Marcellus and I, as the clock struck one— |

| Enter Ghost | The Ghost enters. |

| MARCELLUS: Peace, break thee off; look, where it comes again! | Quiet! Stop talking—look, it’s coming again! |

| BERNARDO: In the same figure, like the king that’s dead. | In the same form—as the dead king! |

| MARCELLUS: Thou art a scholar; speak to it, Horatio. | You’re educated, Horatio—speak to it. |

| BERNARDO: Looks it not like the king? mark it, Horatio. | Doesn’t it look like the king? Look at it, Horatio! |

| HORATIO: Most like: it harrows me with fear and wonder. | Very much so. It chills me with fear and awe. |

| BERNARDO: It would be spoke to. | It seems like it wants to be spoken to. |

| MARCELLUS: Question it, Horatio. | Speak to it, Horatio. |

| HORATIO: What art thou that usurp’st this time of night, Together with that fair and warlike form In which the majesty of buried Denmark Did sometimes march? by heaven I charge thee, speak! | Who are you, that take on this time of night together with that noble, warlike figure the late King of Denmark once wore? By heaven, I order you to speak! |

| MARCELLUS: It is offended. | It’s offended. |

| BERNARDO: See, it stalks away! | Look—it’s walking away! |

| HORATIO: Stay! speak, speak! I charge thee, speak! | Stay! Speak! Speak! I order you to speak! |

| Exit Ghost | The Ghost leaves. |

| MARCELLUS: ’Tis gone, and will not answer. | It’s gone and won’t reply. |

| BERNARDO: How now, Horatio! you tremble and look pale: Is not this something more than fantasy? What think you on’t? | Well, Horatio! You’re trembling and pale. Is this not more than imagination? What do you think of it now? |

| HORATIO: Before my God, I might not this believe Without the sensible and true avouch Of mine own eyes. | I swear to God, I wouldn’t have believed this without the clear and undeniable evidence of my own eyes. |

| MARCELLUS: Is it not like the king? | Isn’t it the spitting image of the king? |

| HORATIO: As thou art to thyself: Such was the very armour he had on When he the ambitious Norway combated; So frown’d he once, when, in an angry parle, He smote the sledded Polacks on the ice. ’Tis strange. | Exactly as you are like yourself. He wore that very armour when he fought the ambitious king of Norway. He wore that same frown when, in a heated encounter, he struck down the sled-mounted Poles on the ice. This is extraordinary. |

| MARCELLUS: Thus twice before, and jump at this dead hour, With martial stalk hath he gone by our watch. | He’s appeared twice before, always at this exact dead hour, marching by us like a soldier. |

| HORATIO: In what particular thought to work I know not; But in the gross and scope of mine opinion, This bodes some strange eruption to our state. | I don’t know what to think in detail, but in general I believe this foreshadows some violent upheaval in our nation. |

| MARCELLUS: Good now, sit down, and tell me, he that knows, Why this same strict and most observant watch So nightly toils the subject of the land, And why such daily cast of brazen cannon, And foreign mart for implements of war; Why such impress of shipwrights, whose sore task Does not divide the Sunday from the week; What might be toward, that this sweaty haste Doth make the night joint-labourer with the day: Who is’t that can inform me? | Please, sit down, and someone who knows, explain to me: Why is there such strict nightly guard duty, exhausting the people? Why are cannons being cast every day, and foreign markets searched for weapons? Why are shipbuilders being forced to work without even a Sunday’s rest? What is brewing that forces such frantic effort, making night work alongside day? Who can explain? |

| HORATIO: That can I; At least, the whisper goes so. Our last king, Whose image even but now appear’d to us, Was, as you know, by Fortinbras of Norway, Thereto prick’d on by a most emulate pride, Dar’d to the combat; in which our valiant Hamlet— For so this side of our known world esteem’d him— Did slay this Fortinbras; who by a seal’d compact, Well ratified by law and heraldry, Did forfeit, with his life, all those his lands Which he stood seized of, to the conqueror: Against the which, a moiety competent Was gaged by our king; which had return’d To the inheritance of Fortinbras, Had he been vanquisher; as, by the same covenant, And carriage of the article design’d, His fell to Hamlet. Now, sir, young Fortinbras, Of unimproved mettle hot and full, Hath in the skirts of Norway here and there Shark’d up a list of lawless resolutes, For food and diet, to some enterprise That hath a stomach in’t; which is no other— As it doth well appear unto our state— But to recover of us, by strong hand And terms compulsatory, those foresaid lands So by his father lost: and this, I take it, Is the main motive of our preparations, The source of this our watch and the chief head Of this post-haste and romage in the land. | I can. Or at least, that’s the rumour. Our late king—the very image we just saw—was, as you know, challenged to single combat by Fortinbras of Norway, who was spurred on by pride. In that duel, our valiant Hamlet (as the world called him) killed Fortinbras. According to a sealed treaty, ratified by law, Fortinbras had to surrender all his lands to the victor. A portion of land had also been staked by our king, which would have gone to Fortinbras if he had won. But since Hamlet won, that land became his. Now, young Fortinbras—fiery, untested, and reckless—has been gathering bands of lawless men on Norway’s borders, desperate types willing to fight for food and pay. His aim, it seems clear, is to take back by force the lands his father lost. And that, I believe, is why we are preparing for war, why guards keep such strict watch, and why the kingdom is so busy night and day. |

| BERNARDO: I think it be no other but e’en so: Well may it sort, that this portentous figure Comes armed through our watch; so like the king That was and is the question of these wars. | I think you’re exactly right. It makes sense that this ominous figure appears during our watch, dressed like the king who was at the heart of those wars. |

| HORATIO: A mote it is to trouble the mind’s eye. In the most high and palmy state of Rome, A little ere the mightiest Julius fell, The graves stood tenantless and the sheeted dead Did squeak and gibber in the Roman streets: As stars with trains of fire and dews of blood, Disasters in the sun; and the moist star, Upon whose influence Neptune’s empire stands, Was sick almost to doomsday with eclipse: And even the like precurse of fierce events, As harbingers preceding still the fates And prologue to the omen coming on, Have heaven and earth together demonstrated Unto our climatures and countrymen. — But soft, behold! lo, where it comes again! I’ll cross it, though it blast me. Stay, illusion! If thou hast any sound, or use of voice, Speak to me: If there be any good thing to be done, That may to thee do ease and grace to me, Speak to me: If thou art privy to thy country’s fate, Which, happily, foreknowing may avoid, O, speak! Or if thou hast uphoarded in thy life Extorted treasure in the womb of earth, For which, they say, you spirits oft walk in death, Speak of it: stay, and speak!—Stop it, Marcellus. | It’s like a speck that troubles the mind’s eye. In Rome, just before mighty Julius Caesar was killed, the graves gave up their dead; the shrouded corpses squealed and chattered in the streets. There were fiery stars, showers of blood, disasters in the sun, and the moon—Neptune’s star—was nearly darkened to doomsday by eclipse. Just like those omens that foretold violent events, signs in heaven and on earth have warned our land and people. But wait—look! Here it comes again! I’ll confront it, even if it destroys me. Stop, phantom! If you have a voice or sound, speak! If there’s something good that I could do for you, something that might give you peace and me honour, speak! If you know of your country’s fate, which we might avoid by knowing in advance, O, speak! Or if in life you hid treasure in the earth, for which, they say, you spirits oft walk in death, Speak of it: stay, and speak!—Stop it, Marcellus. |

| MARCELLUS: Shall I strike at it with my partisan? | Shall I strike it with my spear? |

| HORATIO: Do, if it will not stand. | Do so, if it won’t stop. |

| BERNARDO: ’Tis here! | It’s here! |

| HORATIO: ’Tis here! | It’s here! |

| MARCELLUS: ’Tis gone! | It’s gone! |

| Exit Ghost | The Ghost disappears. |

| HORATIO: We do it wrong, being so majestical, To offer it the show of violence; For it is, as the air, invulnerable, And our vain blows malicious mockery. | We are wrong to try violence against such a majestic being. It’s invulnerable as air, and our blows are a pointless insult. |

| BERNARDO: It was about to speak, when the cock crew. | It was about to speak when the rooster crowed. |

| HORATIO: And then it started like a guilty thing Upon a fearful summons. I have heard, The cock, that is the trumpet to the morn, Doth with his lofty and shrill-sounding throat Awake the god of day; and, at his warning, Whether in sea or fire, in earth or air, Th’extravagant and erring spirit hies To his confine: and of the truth herein This present object made probation. | And then it startled, like a guilty thing summoned in fear. I’ve heard the rooster, the trumpet of the morning, with its shrill call, awakens the god of day; and at that warning, whether in sea or fire, on earth or in air, wandering spirits rush back to their bounds. What we just saw proves this true. |

| MARCELLUS: It faded on the crowing of the cock. Some say that ever ’gainst that season comes Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated, The bird of dawning singeth all night long: And then, they say, no spirit dare stir abroad; The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike, No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm, So hallow’d and so gracious is the time. | It vanished at the cock’s crow. Some say that around Christmas—the time of our Saviour’s birth—the rooster sings all night long. At that time, they say, no spirit dares wander, the nights are harmless, no evil stars strike, no fairies bewitch, no witch casts spells, because the season is so holy and blessed. |

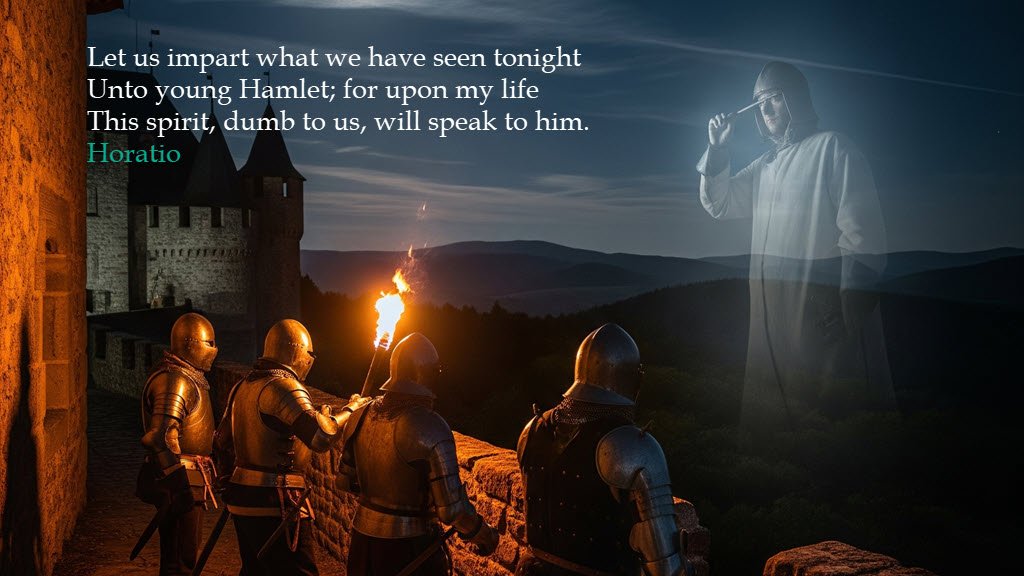

| HORATIO: So have I heard and do in part believe it. But, look, the morn, in russet mantle clad, Walks o’er the dew of yon high eastward hill: Break we our watch up; and by my advice, Let us impart what we have seen to-night Unto young Hamlet; for, upon my life, This spirit, dumb to us, will speak to him. Do you consent we shall acquaint him with it, As needful in our loves, fitting our duty? | I’ve heard that too, and half believe it. But look—the morning, dressed in a red cloak, is walking across the dew of that eastern hill. Let’s end our watch. And I advise we tell young Hamlet what we’ve seen tonight. I’ll wager this spirit, silent to us, will speak to him. Do you agree that, out of affection and duty, we should tell him? |

| MARCELLUS: Let’s do’t, I pray; and I this morning know Where we shall find him most conveniently. | Let’s do it, please. And I know where we can find him most easily this morning. |

| Exeunt | They exit. |

Introductory Notes

Shakespeare’s Hamlet opens not with the eponymous prince, but with a scene of deep unease on the battlements of Elsinore Castle. Act 1, Scene 1 functions as a refined example of dramatic exposition, establishing the play’s dual identity as a revenge tragedy and a psychological study, while immersing the audience in an atmosphere of tension and apprehension.

The opening line, “Who’s there?” is more than a practical question; it introduces the play’s central themes: identity, suspicion, and the pervasive decay of moral and political order. This brief exchange immediately draws the audience into a state of unrest that defines the tone of the entire tragedy.

The scene conveys a large amount of information in a brief span, setting the stage for the central conflict. It introduces important characters, outlines the political instability of Denmark, and presents the supernatural trigger—the ghost of the recently deceased King Hamlet. The stark contrast between the bleak, frigid setting on the castle platform and the festive atmosphere within the castle underscores the central conflict between outward appearances and internal corruption. The very air of Denmark seems tainted, a sentiment that recurs throughout the play.

Atmosphere and Setting: Sickness at the Heart of Denmark

Shakespeare’s Hamlet opens not with the eponymous prince, but with a scene of deep unease on the battlements of Elsinore Castle. Act 1, Scene 1 functions as a refined example of dramatic exposition, establishing the play’s dual identity as a revenge tragedy and a psychological study, while immersing the audience in an atmosphere of tension and apprehension.

The opening line, “Who’s there?” is more than a practical question; it introduces the play’s central themes: identity, suspicion, and the pervasive decay of moral and political order. This brief exchange immediately draws the audience into a state of unrest that defines the tone of the entire tragedy.

The scene conveys a large amount of information in a brief span, setting the stage for the central conflict. It introduces important characters, outlines the political instability of Denmark, and presents the supernatural trigger—the ghost of the recently deceased King Hamlet. The stark contrast between the bleak, frigid setting on the castle platform and the festive atmosphere within the castle underscores the central conflict between outward appearances and internal corruption. The very air of Denmark seems tainted, a sentiment that recurs throughout the play.

Character and Perspective: The Voice of Reason

Horatio’s role in this scene is pivotal and goes far beyond that of a mere witness. Introduced as a “scholar” and a “voice of Reason,” he is brought to the battlements to prove the guards’ story to be “but our fantasy”. His initial skepticism, encapsulated in his line “Tush, tush, ’twill not appear” , is a deliberate literary device.

Shakespeare faced a significant dramatic challenge: how to make a ghost story believable to a Renaissance audience with a wide range of beliefs regarding the supernatural. By introducing a rational, educated character who initially doubts the supernatural event, Shakespeare validates the Ghost’s reality for the audience. Horatio functions as a surrogate for the audience’s own skepticism. When he sees the Ghost, his reaction is not one of casual acceptance but of overwhelming terror and conviction. He confesses, “I would not have believed it without the witness of my own eyes”. This statement moves the scene from the realm of simple superstition into a profound exploration of truth and reality, lending dramatic legitimacy to the entire plot that will hinge on the Ghost’s testimony. Questions on Horatio’s initial attitude and his subsequent reaction are intended to assess a student’s understanding of his crucial role in establishing the play’s credibility.

Political and Thematic Foundations: The Threat from Without

The Fortinbras subplot is not an extraneous detail but a foundational parallel to Hamlet’s central conflict. Through Horatio’s exposition, the audience learns that the late King Hamlet defeated King Fortinbras of Norway in single combat, seizing lands by a “sealed compact”. Now, young Fortinbras is “hot and full” of “unimproved metal” and is raising an army to “recover of us, by strong hand” his father’s lost territory. This political backstory immediately introduces the theme of revenge, setting up a parallel between Fortinbras’s mission to avenge his father and Hamlet’s impending one.

Fortinbras is immediately presented as a “man of action” , creating a direct thematic contrast with Hamlet, whose defining characteristic will become his intellectual over-analysis and delay. This “thought versus action” theme, crucial to understanding Hamlet’s character, is introduced in the very first scene. The Ghost’s appearance in “the very armour” he wore when he defeated the elder Fortinbras physically links the supernatural unrest to the political turmoil, suggesting the two are inextricably linked. Horatio views the Ghost as a “portentous” omen of “strange eruption to our state” , further reinforcing the idea that the political and supernatural worlds are in disarray. The questions on the Fortinbras backstory are designed to ensure students recall and understand this vital political context and its thematic implications.

The Ghost in Context: A Spirit of Health or Goblin Damned?

The Ghost’s appearance introduces the play’s most profound theological and moral dilemma. For a contemporary Elizabethan audience, the Ghost’s nature was ambiguous due to the recent religious upheaval from Catholicism to Protestantism. Catholics, who held a belief in purgatory, would likely interpret the Ghost as a benevolent soul from that realm, seeking a living person’s help to resolve “unfinished business”. In this context, Hamlet’s decision to follow the Ghost’s instructions would be a righteous, albeit difficult, act.

Conversely, in the new Protestant England, the concept of purgatory had been largely denounced. A Protestant audience would therefore view the Ghost with extreme suspicion, considering it a malevolent demon from hell disguised as the dead king to lure a living soul to its damnation. Horatio’s description of the Ghost’s sudden departure at the cock’s crow as acting “like a guilty thing / Upon a fearful summons” reinforces this ambiguity.

This theological ambiguity is the central problem of the play and is the very reason for Hamlet’s famous hesitation. A benevolent ghost from purgatory would justify immediate, righteous revenge. A malevolent demon, however, would require extreme caution, lest Hamlet damn his own soul by obeying its command. Thus, Hamlet’s eventual “procrastination” is not a simple character flaw but a reasoned, if tortured, response to a profound moral and theological problem. The Ghost’s nature, and the subsequent uncertainty, is the core engine of the play’s inaction. Questions that touch upon the Ghost’s physical appearance, its response to the cock’s crow, and the characters’ interpretations of its presence are designed to prompt students to consider these crucial religious and philosophical layers

How well do you know the scene?

The following quiz is designed to ensure a total understanding of every plot element and significant detail within the scene. Each question has been carefully constructed to assess knowledge of character, plot, setting, and thematic foreshadowing, with a limit of three choices. Use blank piece of paper and write down your answers. Then, click on the next toggle below to see the answers.

1. The play opens with a changing of the guard between which two sentinels?

A. Horatio and Marcellus

B. Bernardo and Francisco

C. Marcellus and Francisco

2. What is Francisco’s state of mind as he prepares to go off watch?

A. He is relieved but also “sick at heart.”

B. He is tired but in good spirits.

C. He is jumpy and believes he saw something.

3. Who joins Bernardo on the battlements after Francisco leaves?

A. Horatio and Marcellus

B. Horatio and the Ghost

C. Marcellus and the Ghost

4. What is Horatio’s initial attitude toward the guards’ story about the apparition?

A. He is fearful and believes them immediately.

B. He is skeptical and thinks it is “but our fantasy.”

C. He is indifferent and wishes to return to bed.

5. How many times have Bernardo and Marcellus previously seen the Ghost?

A. Once before

B. Twice before

C. Never before

6. When the Ghost first appears, what does Marcellus instruct Horatio to do?

A. To draw his sword and attack it.

B. To speak to it, because he is a scholar.

C. To go and tell young Hamlet about it.

7. How does the Ghost respond to Horatio’s initial entreaty?

A. It speaks to him in a low voice.

B. It glares at him and gestures to follow.

C. It stalks away without a word.

8. What is Horatio’s physical reaction after the Ghost disappears?

A. He is overjoyed, convinced of the spirit’s truth.

B. He is trembling and as pale as a sheet.

C. He is angered that the Ghost did not speak.

9. What does the Ghost wear that Horatio immediately recognizes?

A. The crown of the late king.

B. The same clothes he was buried in.

C. The armor he wore when he defeated King Fortinbras of Norway.

10. What historical parallel does Horatio draw to the Ghost’s appearance and the state of Denmark?

A. The fall of the Greek city-state of Sparta.

B. The omens that preceded the assassination of Julius Caesar.

C. The military campaigns of Alexander the Great.

11. What is the cause of the military preparations in Denmark that Horatio explains to the others?

A. Young Hamlet is leading a new expedition.

B. Young Fortinbras of Norway is raising an army to reclaim lands lost by his father.

C. King Claudius is preparing for a jousting tournament.

12. Who defeated the elder Fortinbras in combat, leading to the forfeiture of Norwegian lands?

A. Young Fortinbras’s father

B. The late King Hamlet

C. Prince Hamlet

13. What sound causes the Ghost to disappear for the second and final time in the scene?

A. A trumpet blast

B. A soldier’s horn

C. The crowing of a cock

14. What does Horatio believe the Ghost’s departure signifies?

A. That the Ghost is a demon fleeing the sacred time of Christmas.

B. That the Ghost has accomplished its mission.

C. That the Ghost is a “guilty thing” startled by a fearful summons.

15. Horatio says that the Ghost, being so “majestical,” would be done “wrong” by what?

A. Any attempt to speak to it.

B. The suggestion that it is a malevolent spirit.

C. The “show of violence” by the guards.

16. When the Ghost is about to speak for the second time, what does Horatio say caused it to be interrupted and disappear?

A. The sound of the morning watch changing.

B. The sound of a crowing cock.

C. The sound of Hamlet approaching.

17. What is the group’s final decision at the end of the scene?

A. To tell the new King, Claudius, about the Ghost.

B. To inform young Hamlet of what they have seen.

C. To return to their homes and never speak of it again.

18. Why do they believe the Ghost, which was “dumb” to them, will speak to Hamlet?

A. Because Hamlet is the new King.

B. Because Hamlet is its son.

C. Because Hamlet is also a scholar.

19. What time do the guards say they will meet Hamlet on the platform?

A. Between eleven and twelve

B. At dawn

C. The following night at the stroke of twelve

20. Horatio’s description of the Ghost’s behavior as a “guilty thing” introduces which central themes of the play?

A. Love and loyalty

B. Guilt and punishment

C. Hope and despair

Answers

- The play opens with a changing of the guard between which two sentinels?

B. Bernardo and Francisco - What is Francisco’s state of mind as he prepares to go off watch?

A. He is relieved but also “sick at heart.” - Who joins Bernardo on the battlements after Francisco leaves?

A. Horatio and Marcellus - What is Horatio’s initial attitude toward the guards’ story about the apparition?

B. He is skeptical and thinks it is “but our fantasy.” - How many times have Bernardo and Marcellus previously seen the Ghost?

B. Twice before - When the Ghost first appears, what does Marcellus instruct Horatio to do?

B. To speak to it, because he is a scholar. - How does the Ghost respond to Horatio’s initial entreaty?

C. It stalks away without a word. - What is Horatio’s physical reaction after the Ghost disappears?

B. He is trembling and as pale as a sheet. - What does the Ghost wear that Horatio immediately recognizes?

C. The armor he wore when he defeated King Fortinbras of Norway. - What historical parallel does Horatio draw to the Ghost’s appearance and the state of Denmark?

B. The omens that preceded the assassination of Julius Caesar. - What is the cause of the military preparations in Denmark that Horatio explains to the others?

B. Young Fortinbras of Norway is raising an army to reclaim lands lost by his father. - Who defeated the elder Fortinbras in combat, leading to the forfeiture of Norwegian lands?

B. The late King Hamlet - What sound causes the Ghost to disappear for the second and final time in the scene?

C. The crowing of a cock - What does Horatio believe the Ghost’s departure signifies?

C. That the Ghost is a “guilty thing” startled by a fearful summons. - Horatio says that the Ghost, being so “majestical,” would be done “wrong” by what?

C. The “show of violence” by the guards. - When the Ghost is about to speak for the second time, what does Horatio say caused it to be interrupted and disappear?

B. The sound of a crowing cock. - What is the group’s final decision at the end of the scene?

B. To inform young Hamlet of what they have seen. - Why do they believe the Ghost, which was “dumb” to them, will speak to Hamlet?

B. Because Hamlet is its son. - What time do the guards say they will meet Hamlet on the platform?

B. At dawn - Horatio’s description of the Ghost’s behavior as a “guilty thing” introduces which central themes of the play?

B. Guilt and punishment